The second Aztec calendar was the xiuhpohualli or ‘counting of the years’ which was based on a 365-day solar cycle. There was also a class of official diviners who interpreted which dates were the most auspicious for certain events such as marriages, and agricultural chores such as planting particular crops, and which days should be avoided. Records were kept of the days in a book made of bark paper, called a tonalamatl. For this reason, it was possible for Aztec children to be given the name of the day on which they were born. This all seems rather complicated compared to a modern 7-day week of repeating names but it did have the advantage that every single day of the year had its own unique name and number combination and so could not be confused with any other. Finally, in yet another layer of meaning, the 20 days were divided into four groups based on the cardinal points: acatl (east), tecpatl (north), calli (west), and tochtli (south).ĮVERY SINGLE DAY OF THE YEAR HAD ITS OWN UNIQUE NAME AND NUMBER COMBINATION AND SO COULD NOT BE CONFUSED WITH ANY OTHER. On top of that, each group of 13 days was ascribed its own god too. Daylight hours also had their own patron birds such as the hummingbird, owl, turkey, and quetzal, and one day had a butterfly patron. These were taken from the Aztec pantheon and included Tezcatlipoca, Quetzalcoatl, Tlaloc, Xiuhtecuhtli, and Mictlantecuhtli. In addition to names and numbers, each day was also given its own deity – one of thirteen day-lords (the levels of heaven) and one from nine night-lords (the levels of the underworld). The number 260 has multiple significances: it is the approximate human gestation period, the period between the appearance of Venus, and the length of the Mesoamerican agricultural cycle. After all possible combinations of names and numbers had been achieved, 260 days had passed. This meant that each day had both a name and a number (e.g.: 4-Rabbit), with the latter changing as the calendar rotated. The 20-day group ran simultaneously with another group of 13 numbered days (perhaps not coincidentally the Aztec heaven had 13 layers). The calendar was broken down into units (sometimes referred to as trecenas) of 20 days with each day having its own name and symbol: It formed a 260-day cycle, in all probability originally based on astronomical observations. The Aztecs used a sacred calendar known as the tonalpohualli or “counting of the days.” This went back to great antiquity in Mesoamerica, perhaps to the Olmec civilization of the 1st millennium BCE.

It is significant that most major Aztec monuments and artworks conspicuously carry a date of some kind. Time was to be kept, measured, and recorded. (127)įor the Aztecs, specific times, dates and periods, such as one’s birthday for example, could have an auspicious (or opposite) effect on one’s personality, the success of harvests, the prosperity of a ruler’s reign, and so on. The cosmogenic myths reveal a preoccupation with the process of creation, destruction and recreation, and the calendrical system reflected these notions about the character of time.

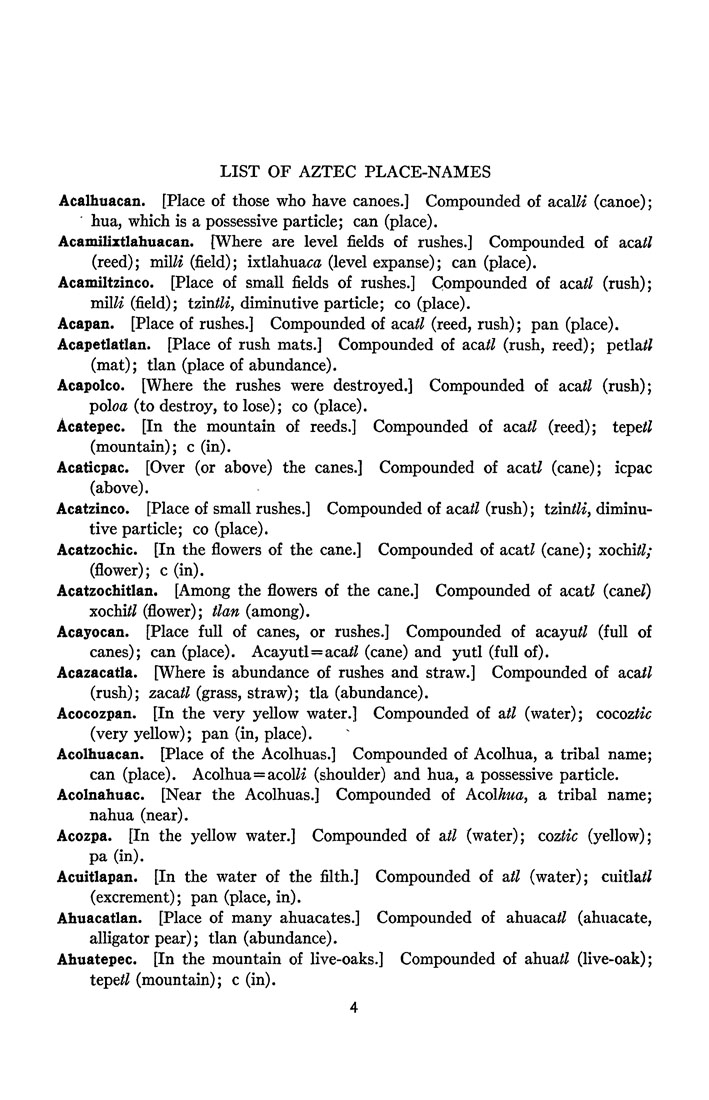

#LIST OF AZTEC NAMES FULL#

Time for the Aztecs was full of energy and motion, the harbinger of change, and always charged with a potent sense of miraculous happening.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)